Full House at New Book Release

April 5, 2016

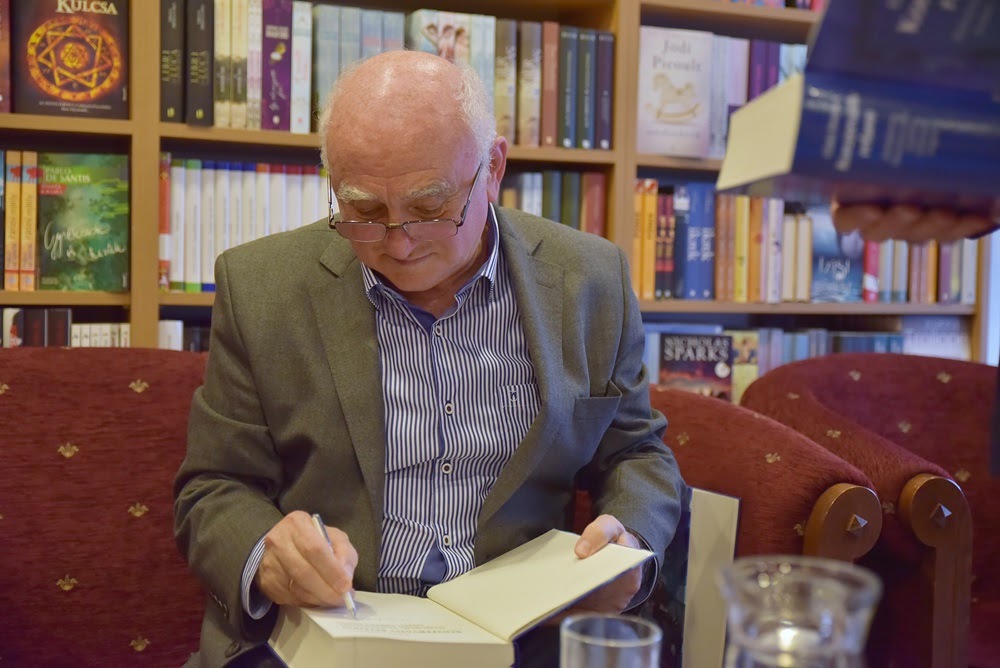

The latest book by historian Ferenc Glatz – Konzervatív reform. Klebelsberg, Domanovszky, Szekfű, Hóman, Hajnal [Conservative Reform. Klebelsberg, Domanovszky, Szekfű, Hóman, Hajnal] – was presented by Prof. György Granasztói at the public book presentation and signing organized at István Örkény Bookstore in Budapest. The release of the new book by Academician Ferenc Glatz attracted a large audience leaving no empty chair at the bookstore’s club. Prominent personalities of Hungarian public life attended the event, among them Academician László Lovász, President of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences; Miklós Németh, Prime Minister of Hungary a. D.; the former President of the State Audit Office of Hungary; numerous former ministers as well as leading officials and members of HAS; present and former leading officials of the Prime Minister’s Office; as well as colleagues and fellow-historians of Hungarian academic life.

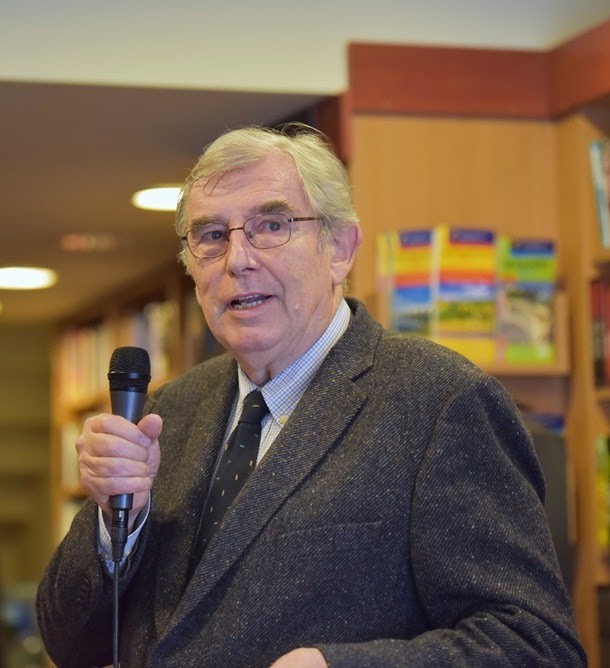

This book offers the reader an imprint of the research attitude of a scholar – an attitude that was characteristic of the every-day life of the author, Ferenc Glatz, and the generations of the 1970s–1990s – said the journalist, Ágnes László, in her introductory speech at the book presentation of Ferenc Glatz’s new book entitled Konzervatív reform. Klebelsberg, Domanovszky, Szekfű, Hóman, Hajnal [Conservative Reform. Klebelsberg, Domanovszky, Szekfű, Hóman, Hajnal]. As the moderator of the event, she continued by saying that, though, the author is well-known to the audience and the wider public as former minister, editor of the periodical História, the President of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences or as head of national strategic research, they may less be acquainted with Ferenc Glatz, the research scholar. The present work goes beyond introducing us to the five protagonists listed in the title – Klebelsberg, Domanovszky, Szekfű, Hóman, Hajnal –, it introduces us to the author himself. Especially, since the studies on the protagonists are supplemented not only by the description of contemporary settings placed in a broader perspective but also by detailed accounts of the research procedures and schedules as well as the personal impressions of the author while he was conducting research on the various topics and relevant source materials. The moderator quoted from the book the sentence “research is everything, the outcome is nothing” as a frame of reference for describing the structure of the chapters, the thematic choice or the genres used as well as the reminiscences of the author added to the chapters which include deeper insights into and an overall analysis of the era. The moderator recapitulated the techniques of research, the circumstances under which research was conducted, the procedures how researchers in earlier times gathered their material and handled available sources. For present generations this might prove especially interesting, since this was way before the internet. The works of a scholar from the beginning of the 20th century could not be deliberately downloaded. One had to travel to Germany, France, Britain, Austria and visit the local libraries to get hold of such works. Also the collection and processing of data and resource materials were done by hand which meant writing down notes on pieces of paper or the learning of pieces of information by heart having, thus, to rely solely on one’s memory.

This book offers the reader an imprint of the research attitude of a scholar – an attitude that was characteristic of the every-day life of the author, Ferenc Glatz, and the generations of the 1970s–1990s – said the journalist, Ágnes László, in her introductory speech at the book presentation of Ferenc Glatz’s new book entitled Konzervatív reform. Klebelsberg, Domanovszky, Szekfű, Hóman, Hajnal [Conservative Reform. Klebelsberg, Domanovszky, Szekfű, Hóman, Hajnal]. As the moderator of the event, she continued by saying that, though, the author is well-known to the audience and the wider public as former minister, editor of the periodical História, the President of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences or as head of national strategic research, they may less be acquainted with Ferenc Glatz, the research scholar. The present work goes beyond introducing us to the five protagonists listed in the title – Klebelsberg, Domanovszky, Szekfű, Hóman, Hajnal –, it introduces us to the author himself. Especially, since the studies on the protagonists are supplemented not only by the description of contemporary settings placed in a broader perspective but also by detailed accounts of the research procedures and schedules as well as the personal impressions of the author while he was conducting research on the various topics and relevant source materials. The moderator quoted from the book the sentence “research is everything, the outcome is nothing” as a frame of reference for describing the structure of the chapters, the thematic choice or the genres used as well as the reminiscences of the author added to the chapters which include deeper insights into and an overall analysis of the era. The moderator recapitulated the techniques of research, the circumstances under which research was conducted, the procedures how researchers in earlier times gathered their material and handled available sources. For present generations this might prove especially interesting, since this was way before the internet. The works of a scholar from the beginning of the 20th century could not be deliberately downloaded. One had to travel to Germany, France, Britain, Austria and visit the local libraries to get hold of such works. Also the collection and processing of data and resource materials were done by hand which meant writing down notes on pieces of paper or the learning of pieces of information by heart having, thus, to rely solely on one’s memory. In the beginning of his book presentation, Professor emeritus György Granasztói, Doctor of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, referred to the same period as mentioned by the moderator, especially since his acquaintance with the author dates back to the aforementioned decades when they were colleagues and friends at the Institute of History of HAS – the venue where the chapters of the present book were actually drafted by Ferenc Glatz. György Granasztói by evoking his personal memories of the young generation of historians in the 1970s–1980s stressed the vivid interest and scientific curiosity in the research and work of the other among the members of this generation. Another important thing that marked the Institute of History in those times was the continuity of upcoming generations. Among the representatives of the older generations he mentioned György Györffy, László Makkai, Kálmán Benda, then came the generation of Jenő Szűcs. The newcomers, thus, perceived of themselves as integral parts of this chain of upcoming generations. György Granasztói’s special field of interest at that time linked him to the older generation of historians in the institute who specialized in economic history, and he was especially interested in the French Annales School, both from a historiographic perspective and in terms of its methodology. For this reason he chose to analyse at his occasion the chapters on Sándor Domanovszky and István Hajnal in depth. He shared the author’s view that István Hajnal was a great thinker. Hajnal pioneered in transplanting the methodology used by sociology on mass phenomena in history. He emphasized the merits of Ferenc Glatz in working out topics of historiographic relevance in the decades from 1969 to 1989, thus, exposing the basic questions of historical recognition and methodology with reference to their source value in political and intellectual history, what’s more in economic and social history as well. György Granasztó also emphasized the relevance of an earlier initiative by Ferenc Glatz, namely the analysis of the oeuvre of European historians from a methodological point of view. He referred in this respect to the oeuvre of the contested German sociologist, Hans Freyer who was closely working together with Hajnal and other Hungarian historians – as thoroughly documented in the book by Glatz – during the years he spent in Hungary after he became disillusioned by National Socialism. In his closing words Professor Gransztói once again referred to the young historians of his generation in the Institute of History and to their curiosity and vivid interest in the various fields of the profession and in public events. In this respect he also mentioned the discussions held twice weekly in the institute and the topics which Ferenc Glatz regularly put on the agenda, namely a thorough analysis of the nature and characteristics of historical writing and of the general factors that an potential impact on the profession as well as those factors which are induced by the actual events and the era at the time a research is conducted or a work is written.

In the beginning of his book presentation, Professor emeritus György Granasztói, Doctor of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, referred to the same period as mentioned by the moderator, especially since his acquaintance with the author dates back to the aforementioned decades when they were colleagues and friends at the Institute of History of HAS – the venue where the chapters of the present book were actually drafted by Ferenc Glatz. György Granasztói by evoking his personal memories of the young generation of historians in the 1970s–1980s stressed the vivid interest and scientific curiosity in the research and work of the other among the members of this generation. Another important thing that marked the Institute of History in those times was the continuity of upcoming generations. Among the representatives of the older generations he mentioned György Györffy, László Makkai, Kálmán Benda, then came the generation of Jenő Szűcs. The newcomers, thus, perceived of themselves as integral parts of this chain of upcoming generations. György Granasztói’s special field of interest at that time linked him to the older generation of historians in the institute who specialized in economic history, and he was especially interested in the French Annales School, both from a historiographic perspective and in terms of its methodology. For this reason he chose to analyse at his occasion the chapters on Sándor Domanovszky and István Hajnal in depth. He shared the author’s view that István Hajnal was a great thinker. Hajnal pioneered in transplanting the methodology used by sociology on mass phenomena in history. He emphasized the merits of Ferenc Glatz in working out topics of historiographic relevance in the decades from 1969 to 1989, thus, exposing the basic questions of historical recognition and methodology with reference to their source value in political and intellectual history, what’s more in economic and social history as well. György Granasztó also emphasized the relevance of an earlier initiative by Ferenc Glatz, namely the analysis of the oeuvre of European historians from a methodological point of view. He referred in this respect to the oeuvre of the contested German sociologist, Hans Freyer who was closely working together with Hajnal and other Hungarian historians – as thoroughly documented in the book by Glatz – during the years he spent in Hungary after he became disillusioned by National Socialism. In his closing words Professor Gransztói once again referred to the young historians of his generation in the Institute of History and to their curiosity and vivid interest in the various fields of the profession and in public events. In this respect he also mentioned the discussions held twice weekly in the institute and the topics which Ferenc Glatz regularly put on the agenda, namely a thorough analysis of the nature and characteristics of historical writing and of the general factors that an potential impact on the profession as well as those factors which are induced by the actual events and the era at the time a research is conducted or a work is written. Ferenc Glatz in his attempt to answer all the questions and issues raised by György Granasztói and the moderator began with stating that in his earlier years he was in fact inclined, as most members of his generation, to conduct ‘l’art pour l’art’ historical research’. Instead of the formally stiffened annual celebrations of political events and the construction of statue-like ”memorial-history-writing” – which was in fashion in political life from the 1960s onwards– he wanted to adopt and pursue his individual programme of writing history based on the principle that history is a repository of the multiplicity mankind and nature is capable of producing and the very worthiness of depicting and analysing such a multiplicity per se – independent of the proclamations of actual political programmes or ideologies… An issue that he elaborated on in his chapter on Kuno Klebelsberg: during the 1920s politics interfered with the profession by overtly promoting ideological programmes – among others by adhering to such thematic preferences as state, nation and national issues – and by financial pressure. (Even scholars specialized right from the beginning in medieval studies were forced to give up their research field and turn to modern history instead.) Even though scholarship was coerced into adapting itself to contemporary cultural policy, it managed to produce longstanding and valuable scholarly achievements – something that teaches us an important lesson –, especially on the history of the 19th century, i.e. the age of nation-building and the establishment of the nation state. This was only possible because the profession and work of the historian, the autonomy of scholarly research and concept creation was, after all, very much acknowledged. This attitude of contemporary cultural policy with its unconditional esteem for keeping standards high also contributed to making Hungarian historical writing one of the most multi-faceted national historical writings in Europe and to laying the foundations of professional scholarly research on modern history – as the author of the book proved in his comparative analysis with the historical writings of other European countries. (This is the reason why he back in 1969 when he was a researching scholar held Kuno Klebelsberg in great esteem or – as it is described in the book – later in 1989 when he became minister and also in 1999 when he was elected President of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. And he wished to keep away cultural and scientific policy from committing the mistake of using administrative measures as means of interfering with thematic preferences or of formulating pre-conceptions with respect to potential research outcomes.)

Ferenc Glatz in his attempt to answer all the questions and issues raised by György Granasztói and the moderator began with stating that in his earlier years he was in fact inclined, as most members of his generation, to conduct ‘l’art pour l’art’ historical research’. Instead of the formally stiffened annual celebrations of political events and the construction of statue-like ”memorial-history-writing” – which was in fashion in political life from the 1960s onwards– he wanted to adopt and pursue his individual programme of writing history based on the principle that history is a repository of the multiplicity mankind and nature is capable of producing and the very worthiness of depicting and analysing such a multiplicity per se – independent of the proclamations of actual political programmes or ideologies… An issue that he elaborated on in his chapter on Kuno Klebelsberg: during the 1920s politics interfered with the profession by overtly promoting ideological programmes – among others by adhering to such thematic preferences as state, nation and national issues – and by financial pressure. (Even scholars specialized right from the beginning in medieval studies were forced to give up their research field and turn to modern history instead.) Even though scholarship was coerced into adapting itself to contemporary cultural policy, it managed to produce longstanding and valuable scholarly achievements – something that teaches us an important lesson –, especially on the history of the 19th century, i.e. the age of nation-building and the establishment of the nation state. This was only possible because the profession and work of the historian, the autonomy of scholarly research and concept creation was, after all, very much acknowledged. This attitude of contemporary cultural policy with its unconditional esteem for keeping standards high also contributed to making Hungarian historical writing one of the most multi-faceted national historical writings in Europe and to laying the foundations of professional scholarly research on modern history – as the author of the book proved in his comparative analysis with the historical writings of other European countries. (This is the reason why he back in 1969 when he was a researching scholar held Kuno Klebelsberg in great esteem or – as it is described in the book – later in 1989 when he became minister and also in 1999 when he was elected President of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. And he wished to keep away cultural and scientific policy from committing the mistake of using administrative measures as means of interfering with thematic preferences or of formulating pre-conceptions with respect to potential research outcomes.)At the beginning of his career, one of the most important self-imposed professional life programmes of the author was to introduce the audience of Hungarian and international forum sites to the merits of the culture of the Hungarian nation which – due to the achievements of the period between 1920 and 1949 – truly matched and has matched up to the present day European standards. “It goes without saying that a historian who is a scholar committed to his profession and not a disseminator of political agitprop shall not align with ideological programmes or venture into drafting counter-programmes; it is, however, equally true that the disclosure of facts, the actual fact-finding, or the conclusion which the historian had arrived at during the course of his research will, after all, stand on its own in its contemporary intellectual setting – being, thus, detached from the historian him- or herself ” – said Glatz. He mentioned as an example Szekfű’s work Három nemzedék [Three generations] which unintended by the author became the “handbook” used in antisemitism campaigns in the 1920s, whilst the public failed to pay attention to the subtle but substantial conclusions of Szekfű as regards the history of ideas and social history. Later, though, the research results and conclusions of Szekfű’s generation finally found their way – independent of the intentions of the individual scholars and authors – into the intellectual setting of the cultural policy of the 1970s and 1980s.

Glatz declared that right from the beginning he made it his self-imposed programme to find a way how to restore high standard book-series and the works of professionally high standard individuals to the cultural political and historical scholarship canon, and this referred to those oeuvres which after 1949 were either denounced or publicly exiled from Hungarian intellectual life. The present book bears testimony to the outcome of this ambition: by the 1970s and 1980s, the europeanness and the scholarly professionalism of the cultural political programme of Kuno Klebelsberg as well as the scholarly innovations of historians who were either exiled from the Academy in 1949 (Domanovszky, Hajnal) or were effaced altogether (Szekfű) were successfully brought back to public consciousness. The present book is not only about the five personalities enlisted in the title (Klebelsberg, Domanovszky, Szekfű, Hóman, Hajnal) or the generation they belonged to, thus, about the period between 1920 and 1949, but also about their step-by-step rehabilitation lasting from 1968 to 1990. Glatz emphasized that during all these decades there existed a prevailing criticism of the expulsion practices of the dictatorship of the proletariat and a constant demand for the introduction of corrective measures. The scholarly lectures and studies in the present book were not circulated “illegally” in samizdat editions but were spoken out loud at public events or appeared in publications available for the public. And in every single case the author took responsibility for what he said or wrote and could, thus, be held accountable for it. He also added that it speaks for itself that those who were actually involved in reforming the system were very much willing to take upon themselves and to support the programme of the rehabilitation of bourgeois culture. This way it became possible to uphold the continuity of generations in historical scholarship – a tradition which also György Granasztói praised –and to restore the continuity of scholarly professionalism between the historical scholarship of the bourgeois era prior to 1949 and the 1970s and 1980s. Glatz remembered György Ránki, the renowned personality of Hungarian and international historical scholarship also known for his merits in science organization, who was a supporter of this programme, both professionally and from a cultural political perspective and Iván T. Berend, the head of the historical and philosophical department at the Academy from1980, later between 1985 and 1990 President of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences and also member of the Central Committee of the Hungarian Socialist Workers Party, since both of them would provide a certain kind of protection for the radical-minded reform initiatives of younger generations.

Ferenc Glatz cited three factors of the period which proved imperative for his generation and himself personally. (He uses the self-coined term metaphontic in this context meaning that, though, these factors lay beyond the framework of academic research and scholarship, they very much had an impact on public thinking and that of the historian.) The three factors mentioned were as follows: 1. Soviet occupation and the Cold War, 2. Trianon and its effect on society, 3. social restructuring after 1920.

The first of the so-called time factors mentioned was the Soviet occupation (1945–1990) and according to Glatz this was probably one of the most stubbornly persistent experiences of his life. Being in his teenage years back then, the suppression of the 1956 uprising, the experience of being left on one’s own evoked in him the recognition that after the lost world war the occupants had, after all, entered Hungarian soil with the consent of the international community and the alliance between the Western powers and the Soviets was firm enough to hold. Consequently, scholars, teachers and artists specialized in historical scholarship, literature or in any topic that would keep the national culture alive would have to prevail in Hungary and adjust the goals they wished to pursue in their individual life to match the framework imposed on the country during the Soviet occupation. “As to our individual life goals, they may occasionally have come up in our discussion, but most of the time, they did not” – said Glatz. There was a set of other goals, though, which we wished to live up to: the standard of the national culture had to be upheld and preserved, the institutions of Hungary’s small national culture had to be kept functioning, the top achievements of other cultures from all over the world had to be introduced at home and the achievements of Hungary as a small national culture had to be propagated all over the world and especially at international professional forum sites. The lost war, the ongoing Cold War and the occupation of the country by Soviet forces meant at that time that Hungarian intellectual life was cut off from the rest of the world. Consequently, soon after Glatz became a researcher the life programme he personally cherished was to tear a crack on the “intellectual iron curtain” – a term he used in his younger years – “and to build passages between East and West, hoping this way to restore the continuity that had prevailed for several hundred years between the culture of the Hungarian nation and that of Europe as well as the rest of the world”.

The other time factor mentioned by Ferenc Glatz was Trianon which not only meant the mutilation of the territorial integrity of Hungary but also the dismemberment of one-third of the nation and its annexation by the hostile neighbouring nation states. His view on this issue – which he has elaborated on numerous times at international events – has not changed since then: the peace system of the years 1919–1920 greatly contributed to the invigoration of national and social radicalism, of social groups thinking along racial lines and of antisemitism in the Central European region – in Germany, Austria, Hungary, i.e. the defeated countries of WW I – and by 1944 these ideas and groupings all rose to power. “Looking at it from this perspective, Clemenceau bears in a certain sense responsibility for the rise of Hitler. And not merely for the renewed outbreak of wars between the states but also for the spreading of social and racial radicalism” – said Glatz. It is also for this reason why the book centres on the concepts of nation and state as well as Trianon and its revision. It is important to note that the thematic choice of the author’s works having evolved in the course of the past decades does not have its roots in nationalistic pre-conceptions of any kind but rather in the research he has conducted and the conclusions he has arrived at during his investigations on common thinking about history and historical concepts in the decades between 1920 and 1945 and on scholarly works on the history of and about this period as well as on contemporary source materials.

As to the third time factor characterising the period under discussion, namely the social revolutions, they in fact had an immediate influence of the life of the author. Nevertheless, since this factor does not belong to the issues discussed in this book, at this point he focussed on the evolvement of the social layer of intellectuals who make a living based on their schooling and educational background – this social layer constituted the backbone of historical scholarship and intellectual life in Hungary between the two world wars. (Except for Hóman who diverted from the original goals and Klebelsberg who died at an early age, the representatives of this generation were stakeholders of the bourgeois democratic era between 1945 and 1948, only to be banned or eliminated from public, political, cultural and academic life by the dictatorship of the proletariat after 1949. The author said that his attempt was to prove that on the long run Domanovszky, Szekfű – who finally agreed to become Hungary’s ambassador to Moscow –, and later Hajnal appeared to have adapted themselves to the newly introduced democratic system. These new generations of the modern bourgeois intellectuals who relied on their education for making a living – with respect to the social transitions following 1945, it was also György Ránki as well as Szűcs and his generation who should be mentioned here – became actively involved in the intellectual and also political life of the 1960s–1980s. By referring to the remarks of György Granasztói on the merits of István Hajnal, Glatz stressed that he considers himself fortunate that at the time he was minister in 1989–1990 he had the opportunity to nominate post mortem István Hajnal for the newly founded Széchenyi Prize, which was set up by the Németh-government, this taking place in the aftermath of the rehabilitation procedures of those historians who were banned in 1949. As to his argumentation back then: the only way to safeguard the persistence of europeanness and the small national culture is when politics shows willingness to openly support the demand for professionalism and, as regards the intellectual life of the country, to uphold continuity in the national culture based on values, and when politics refrains from imposing on intellectuals the burden of having to serve such ideologies of party policy which change on a day-to day basis.

As to the third time factor characterising the period under discussion, namely the social revolutions, they in fact had an immediate influence of the life of the author. Nevertheless, since this factor does not belong to the issues discussed in this book, at this point he focussed on the evolvement of the social layer of intellectuals who make a living based on their schooling and educational background – this social layer constituted the backbone of historical scholarship and intellectual life in Hungary between the two world wars. (Except for Hóman who diverted from the original goals and Klebelsberg who died at an early age, the representatives of this generation were stakeholders of the bourgeois democratic era between 1945 and 1948, only to be banned or eliminated from public, political, cultural and academic life by the dictatorship of the proletariat after 1949. The author said that his attempt was to prove that on the long run Domanovszky, Szekfű – who finally agreed to become Hungary’s ambassador to Moscow –, and later Hajnal appeared to have adapted themselves to the newly introduced democratic system. These new generations of the modern bourgeois intellectuals who relied on their education for making a living – with respect to the social transitions following 1945, it was also György Ránki as well as Szűcs and his generation who should be mentioned here – became actively involved in the intellectual and also political life of the 1960s–1980s. By referring to the remarks of György Granasztói on the merits of István Hajnal, Glatz stressed that he considers himself fortunate that at the time he was minister in 1989–1990 he had the opportunity to nominate post mortem István Hajnal for the newly founded Széchenyi Prize, which was set up by the Németh-government, this taking place in the aftermath of the rehabilitation procedures of those historians who were banned in 1949. As to his argumentation back then: the only way to safeguard the persistence of europeanness and the small national culture is when politics shows willingness to openly support the demand for professionalism and, as regards the intellectual life of the country, to uphold continuity in the national culture based on values, and when politics refrains from imposing on intellectuals the burden of having to serve such ideologies of party policy which change on a day-to day basis.